Lower Rainfall and Less Farm Runoff This Year Contributed to Fewer Locations Exceeding EPA’s Recommendations for Safe Swimming

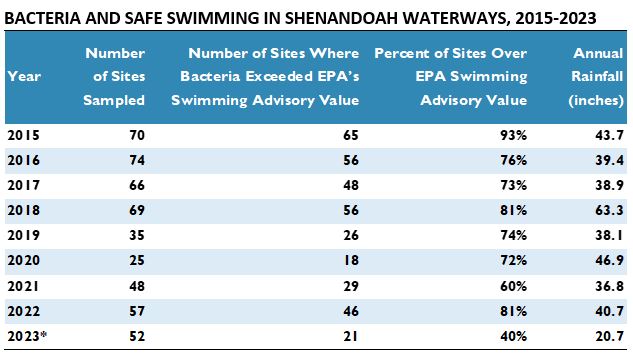

Washington, D.C. – Water quality monitoring at 40 percent of the locations tested in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley this year detected levels of fecal bacteria that made the waters unsafe for swimming, tubing, kayaking, or rafting.

So far this year, 21 of the 52 water monitoring locations in the valley have had levels of E. Coli bacteria that exceeded the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s recommendations for swimming or water contact recreation, according to Virginia Department of Environmental Quality data reviewed by the Environmental Integrity Project.

The percentage of sites with unhealthy bacteria levels was the lowest in the last eight years, in part because the amount of rainfall this year was also the lowest over that period. The 20 inches of rain recorded in Harrisonburg, in the heart of the Shenandoah Valley, from January through August, was a third less than the average of 30 inches. Less rainfall means less manure is washed off farm fields and into streams and rivers.

“The health risks from farm manure runoff were somewhat reduced this summer because of the low rainfall conditions,” said Eric Schaeffer, Executive Director of the Environmental Integrity Project. “This does not mean the Shenandoah River is cleaned up, or that the problem of farm runoff pollution is solved. Virginia should keep up its efforts to convince farmers to fence their livestock out of streams and reduce their overapplication of manure.”

The Shenandoah Valley has the largest concentration of livestock operations in Virginia, with almost 528,000 cows, 160 million chickens, and 16 million turkeys raised annually in Augusta, Page, Shenandoah and Rockingham counties. Most of their manure is spread on surrounding farmland as fertilizer, but it contains far more phosphorus than crops need for growth. The excess manure leaks pollutants into groundwater and is washed by rain into streams.

“Countless businesses and people in the Shenandoah Valley rely upon having a clean, healthy river system,” said Mark Frondorf, the Shenandoah Riverkeeper. “These figures demonstrate that more needs to be done in the way of stream exclusionary fencing on farms, enhancement of buffers of trees and vegetation along streams, and a commitment of both the General Assembly and the agricultural community to put best management practices in place to make the river healthier for everyone. A healthy economy and a healthy environment must walk hand in hand.”

In 2022, the Virginia General Assembly approved a record $265 million for fiscal years 2023 and 2024 for farm pollution-control “best management practices” – including streamside livestock fencing and other steps to reduce runoff into waterways.

As a result of the increased state funding, a growing number of farmers in Virginia have been enrolling in a state program to install livestock fencing. Statewide, 626 farmers signed up for the livestock fencing program in the year that ended July 1, including 33 in August and Rockingham Counties, according to data from the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation.

The threshold value used in this chart is EPA’s “beach action value” for swimming, which recommends states warn the public when bacteria levels exceed 235 counts of E. coli/100 ml water. * Numbers for 2023 are for January through August and reflect data available as of September 18, 2023. Sources: National Water Monitoring Council’s Water Quality Portal and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

A report by the Environmental Integrity Project and Shenandoah Riverkeepers in 2019 found that only 19 percent of the livestock farms in the Shenandoah Valley’s biggest livestock counties – Augusta and Rockingham — had fenced their cattle out of streams, which prevents cows from defecting in waterways and kicking in sediment.

This low fencing rate was despite a pledge by the state of Virginia to EPA that 95 percent of streams through pastures would have livestock fencing by 2025 to meet the goals of the state’s cleanup plan for the Chesapeake Bay.

The release of the report by EIP and Shenandoah Riverkeeper helped to spur Virginia lawmakers to boost state funding to pay for streamside livestock fencing on farms.

For more details about bacteria monitoring in the Shenandoah Valley, click here.

The Environmental Integrity Project is a nonprofit organization, based in Washington D.C. and Austin, Texas, that is dedicated to enforcing environmental laws and strengthening policy to protect public health and the environment.

Media contacts:

Tom Pelton, Environmental Integrity Project, (443) 510-2574 or tpelton@environmentalintegrity.org

Mark Frondorf, Shenandoah Riverkeeper, (571) 969-0746 or mark@shenandoahriverkeeper.org