Washington, D.C. – EPA air monitoring data at the fencelines of oil refineries, available for the first time in 2019, showed that 10 refineries across the U.S. were releasing cancer-causing benzene into nearby communities at concentrations above federal action levels.

These refineries with excessive levels of benzene detected at their perimeters are not in violation of the law. However, the facilities are required by 2015 EPA regulations to conduct analyses of the causes of the toxic emissions and then take action to reduce the pollution.

“These results highlight refineries that need to do a better job of installing pollution controls and implementing safer workplace practices to reduce the leakage of this cancer-causing pollutant into local communities,” said Eric Schaeffer, Executive Director of the Environmental Integrity Project. “EPA in 2015 imposed regulations to better monitor benzene and protect people living near refineries, often in working-class neighborhoods. Now, EPA needs to enforce these rules.”

According to a new report by the Environmental Integrity Project, the refinery with the highest levels of benzene detected at its fencelines, out of more than 100 examined, was the Philadelphia Energy Solutions (PES) refinery in Pennsylvania, which emitted benzene at nearly five times the EPA action level, on average, in the year ending September 30, 2019, according to EPA records. The Philadelphia refinery shut down last June after erupting in explosions and fires.

Second worst in the U.S. was the Holly Frontier Navajo Artesia refinery in Artesia, New Mexico, where monitors at the plant’s fenceline detected benzene in amounts four times the EPA action level. Overall, six of the 10 refineries releasing excessive amounts of benzene were in Texas, including the Total Refinery in Port Arthur, Pasadena Refining outside Houston, and Flint Hills Resources in Corpus Christi, EPA records show.

“This report shows that almost half of the refineries with the most cancer causing benzene emissions in the U.S. are right here in Houston’s backyard,” said Dr. Bakeyah Nelson, Executive Director of Air Alliance Houston. “Governor Abbott needs to get serious about this issue today and direct the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to crack down on this dangerous pollution to protect the health of our families and neighbors, especially communities of color and low-income neighborhoods who are shouldering the burden of disproportionate exposures and impacts on their health.”

EPA’s benzene regulations have their origin in a 2012 lawsuit that the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP) and allies filed on behalf of seven community and environmental groups, including Air Alliance Houston and the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. The lawsuit complained that EPA missed its deadline to review and update toxic air standards for oil refineries by more than a decade.

For years, these local groups had been fighting for stronger protection from refinery pollution, including problems associated with flaring and malfunctions. In response, EPA imposed new regulations for oil refineries designed to reduce the amount of hazardous pollution these companies spew into the air. The new rules, first implemented in 2018, require refineries to set up monitors around the perimeter of their plants to measure concentrations of benzene leaving the property.

As part of the monitoring requirement, refineries must collect air samples at the plant fenceline every two weeks. Refineries then determine the amount of benzene actually coming from the facility by correcting for background or any nearby or offsite sources. If the highest measurement of benzene coming from the facility exceeds an average of 9 micrograms per cubic meter of air over a one-year period, the EPA regulations require the facility to conduct an analysis to determine the root cause of the problems causing the toxic emissions and to then take action to lower those concentrations.

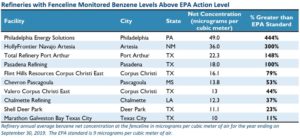

After the first full year of the program, EIP examined the monitoring reports for 114 refineries across the U.S., which are now publicly available on EPA’s website. As of the end of the third quarter of 2019 (which ended on September 30, 2019), EIP found 10 refineries that averaged benzene levels at the fenceline that exceeded the EPA action level. Those refineries are listed in the chart below:

Some of the benzene levels detected in 2018-2019 were extremely high and close to vulnerable populations. For example, in Artesia, New Mexico, at the fenceline of the Holly Frontier Navajo refinery, a monitor in June and July of 2018 detected benzene in a concentration of 1,000 micrograms per cubic meter only three football fields from children at Roselawn Elementary School. That level was more than 30 times the concentration that the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry has concluded could present a health risk, even for short-term exposure.

The surrounding community, within one mile of the Artesia refinery, has 3,318 residents, 74 percent of whom are Hispanic and most of whom live below the poverty line, according to EPA data.

“This report confirms the oil and gas industry is poisoning the air of New Mexican communities with cancer-causing benzene,” said Rebecca Sobel, Senior Climate and Energy Campaigner for WildEarth Guardians. “With air quality suffering throughout New Mexico because of unchecked fracking, it’s time to rein in this mess and hold these companies accountable to our health and safety.”

In Pennsylvania, near the Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery, a monitor detected benzene levels in July 2019 at 190 micrograms per cubic meter just two tenths of a mile from a shopping center. More than 5,100 people live in the area within a mile of the refinery. Half of these local residents are African American and more than two-thirds live in poverty.

“While I’ve worked for years to tackle air pollution as PennEnvironment’s Executive Director, this issue strikes particularly close to home for me since I live less than two miles from the refinery,” said David Masur, Executive Director of Penn Environment. “Raising my two young children is the shadow of the refinery is a stark reminder to the health risks this facility–and others like it–pose.”

Anne Rolfes, Director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, an environmental advocacy group, complained that the people of Chalmette, Louisiana, are being exposed to benzene from the Chalmette Refining plant at dangerous levels. The benzene concentration detected along the refinery fenceline in 2019 was 37 percent higher than EPA action levels.

“It should not require a federal intervention for Chalmette Refining to take action on a cancer causing chemical like benzene,” Rolfes said. “Chalmette Refining’s reckless release of benzene threatens the people who live in the neighborhood right across the street, and a school that is less than a mile away.”

Benzene is a colorless or light yellow chemical with a slightly sweet odor that evaporates from gasoline and oil. It is also manufactured as an ingredient in plastics, pesticides and other products. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, benzene exposure can cause vomiting, headaches, anemia, increased risk of cancer, and – in high enough doses – death.

EPA cautions that the fenceline monitoring action level it established in 2015 is not directly tied to ambient air standards or health-based risk analysis. However, the 10 refineries shown in the table above have long-term benzene concentrations that are more than three times higher than California’s long-term exposure limit for increased risk of blood disorders and other disease. When compared to other benchmarks established by EPA, some of the highest emitting refineries on the list of 10 could represent an additional cancer risk of 4 in 10,000, when considering lifetime exposure.

The 2012 lawsuit against EPA over refinery benzene emissions was filed by the Environmental Integrity Project and Earthjustice on behalf of Air Alliance Houston; Louisiana Bucket Brigade; California Communities Against Toxics; Coalition for a Safe Environment; Community In-Power Development Association; Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services; and Del Amo Action Committee.

In response to the 2015 regulations, both industry and environmental filed challenges to the refinery rules. The Trump EPA this week released a response to the challenges that kept the fenceline monitoring requirement in place. EIP’s report documents why it is important for this monitoring to continue to protect public health.

For a copy of EIP’s report on fenceline monitoring of benzene, click here.

To listen to audio of our February 6, 2020, telephone press conference on the report, click here.

The Environmental Integrity Project is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization based in Washington, D.C., and Austin, Texas, that protects public health and the environment by investigating polluters, holding them accountable under the law, and strengthening public policy.

The Louisiana Bucket Brigade uses grassroots action to create an informed, healthy society that holds the petrochemical industry and government accountable for the true costs of pollution to hasten the transition from fossil fuels.

Air Alliance Houston is a non-profit advocacy organization working to reduce the public health impacts of air pollution and advance environmental justice.

PennEnvironment is a statewide, citizen-based non-profit environmental group working to promote clean air, clean water, and protecting Pennsylvania’s natural heritage. For more information, visit www.PennEnvironment.org.

WildEarth Guardians is a nonprofit environmental advocacy organization dedicated to protecting and restoring the health of the American West.

Media contacts:

Tom Pelton, Environmental Integrity Project (443) 510-2574 or tpelton@environm915stg.wpenginepowered.com

Anne Rolfes, Louisiana Bucket Brigade, (504) 484-3433 or anne@labucketbrigade.org

Riikka Pohjankoski, Air Alliance Houston, (713) 528-3779 or riikka@airalliancehouston.org

David Masur, PennEnvironment, (267) 303-8292 or david@pennenvironment.org

Rebecca Sobel, New Mexico WildEarth Guardians, (267) 402-0724 or rsobel@wildearthguardians.org