Washington, D.C. – Three quarters of large U.S. meat processing plants that discharge their wastewater directly into streams and rivers violated their pollution control permits over the last two years, with some dumping as much nitrogen pollution as small cities – and facing little or no enforcement.

The nonprofit Environmental Integrity Project (EIP) examined EPA records for 98 large meat-processing plants that released more than 250,000 gallons per day into waterways from January 2016 through June 2018 and found that 74 of the plants had exceeded their permit limits for nitrogen, fecal bacteria, or other pollutants at least once. More than half of the plants (50 of 98) had five violations, and a third (32 of 98) had at least 10 violations, according to the EPA data.

EIP’s new report, “Water Pollution from Slaughterhouses,” with research from Earthjustice, also discovered that 60 of the 98 plants release their wastewater to rivers, streams, and other waterways that are impaired because of the main pollutants found in slaughterhouse wastewater: bacteria, pathogens, nutrients, and other oxygen-depleting substances.

“This water pollution is really an environmental justice issue, because many of these slaughterhouses are owned by wealthy international companies, and they are contaminating the rivers and drinking water supplies of rural, often lower-income, minority communities,” said Eric Schaeffer, Executive Director of the Environmental Integrity Project.

“State environmental agencies need to start cracking down on and penalizing these flagrant violations of the federal Clean Water Act,” said Schaeffer, former Director of Civil Enforcement at EPA. “And EPA needs to step in and set stronger national water pollution standards for meat processing plants.”

Peter Lehner, senior attorney at Earthjustice, said: “Slaughterhouses are another dirty link in the highly polluting industrial meat production chain. From polluted runoff from over-fertilized fields growing animal feed, to often-leaking manure lagoons and contaminated runoff at concentrated animal feeding operations, and to industrial slaughterhouses, the way most of our meat is now produced impairs our drinking water and public health. We need to clean up every stage.”

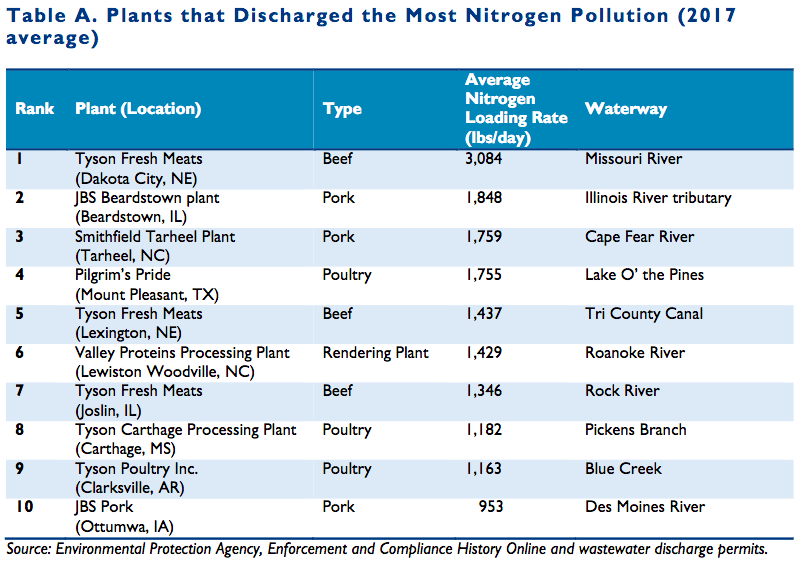

The report ranks the worst polluters in the U.S. in terms of total nitrogen pollution (which fuels excessive algae growth and creates fish-killing low-oxygen “dead zones”). The second most polluting slaughterhouse in U.S. last year was the JBS pork processing plant in Beardstown, Illinois, which released 1,849 pounds of nitrogen a day, on average, into a tributary to the Illinois River. That was equivalent to the load in raw sewage from a city of 79,000 people, according to EPA data. The pork plant, once owned by Cargill but now owned the Brazilian-based international meat company JBS, was also responsible for a spill of 29 million gallons of hog waste in March, 2015, which killed almost 65,000 fish.

“State and federal regulations are far too lax for polluters like JBS that are dumping huge quantities of nitrogen pollution into our streams and rivers,” said Carol Hays, Ph.D., Executive Director of Prairie Rivers Network. “The state needs to pass nitrogen pollution standards and make sure slaughterhouses do their share to reduce nutrient pollution.”

The second worst polluter was the Smithfield Tarheel Plant pork slaughterhouse in Tarheel, North Carolina – the largest hog slaughterhouse in the U.S. — which discharged 1,759 pounds of nitrogen a day, on average, into the Cape Fear River last year, according to the report.

“Why should we let a massive billion-dollar Chinese owned conglomerate – the owners of Smithfield Foods — put our drinking water at risk?” asked Drew Ball, State Director for Environment North Carolina. “The industry has been aware of more sustainable methods for years but Smithfield has failed to modernize their practices in North Carolina, even though they have done so in other states.”

For a list of the worst polluters, see chart at bottom. For a detailed list of all 98 slaughterhouses studied, click here.

EIP’s research found that many of the plants that are not violating their permits are actually discharging more pollution than those breaking the law by failing to comply. In such cases, EPA and state agencies are setting permit limits that allow the discharge of far too much pollution to protect waterways for swimming, fishing or other public uses.

Sixty-five of the 98 meat processing plants that the Environmental Integrity Project examined slaughter chickens, 15 process beef; 9, hogs; and the rest, other meat. The results detailed in the “Water Pollution from Slaughterhouses” report include:

- Tyson Foods owns the most plants (26) with water pollution permit violations last year; followed by Pilgrim’s Pride (7); Sanderson Farms (6); JBS (4); Wayne Farms (4) and Smithfield (3).

- One third (32 of 98) of the plants have had 10 or more permit violations since January 2016. Among the most frequent violators was the FB Purnell Sausage Co. plant in Simpsonville, Kentucky (109 violations).

- Penalties and enforcement are rare. At least 18 slaughterhouses among those studied racked up more than 100 violations per day from 2016 to 2018. But so far, eight of those 18 have not paid any fines at all during this time period.

- The median slaughterhouse discharged an average of 331 pounds of total nitrogen per day, on average, in 2017, as much as the amount contained in raw sewage from a town of 14,000 people.

- Almost half of the slaughterhouses are in communities with more than 30 percent of their residents living beneath the poverty line (more than twice the national level), and a third of the plants are in places where at least 30 percent of the residents are people of color.

The report examines case studies in Delaware, Florida, and Illinois, where local residents have suffered from contaminated drinking water wells, fish kills, tainted rivers and other severe impacts of slaughterhouse pollution.

The EIP report notes that not all of the slaughterhouses are poorly run or in violation of their permits. The most polluting plants in EIP’s study released about thirty times more nitrogen per gallon than the cleanest plants.

“This a sign that these dirty slaughterhouses can improve substantially simply by installing wastewater treatment systems already used by their competitors,” said Eric Schaeffer of EIP. “Requiring these improvements across the U.S. would level the playing field for the industry, while improving protections for waterways and public health.”

The study found that state regulators – often burdened by budget cuts and limited staffing – are often behind in developing cleanup plans for impaired waterways as required by the federal Clean Water Act. Lacking cleanup plans (also called Total Maximum Daily Loads or “TMDL’s”), state regulators are not setting strong enough pollution limits in the permits that they issue to slaughterhouses.

In 40 of the 98 cases EIP examined, the states have not yet established cleanup plans for local waterways to reduce pollution from slaughterhouses and other sources by the amounts needed to restore the rivers and streams to health.

MORE COMMENTS FROM LOCAL RESIDENTS AND CLEAN WATER ORGANIZATIONS:

DELAWARE: Maria Payan, a Delaware resident and consultant for the Socially Responsible Agricultural Project, said: “The people of Sussex County, Delaware – especially the working families who live near the five slaughterhouses in this county – have been unfairly targeted for contamination by industrial poultry operations. It’s reprehensible that the state continues to allow processing plants to expand and use cheap wastewater disposal systems that contaminate our drinking water wells and waterways. Many neighbors of these plants cannot get a glass of clean water from their faucet, swim in public waters, or breathe clean air.”

PENNSYLVANIA: Ted Evgeniadis, the Lower Susquehanna Riverkeeper, said: “The degradation of water quality from slaughterhouse wastewater is serious business, especially when these slaughterhouses continue to exceed their pollutant limits in their state issued water pollution control permits. That is a direct violation of the Clean Water Act. These exceedances, particularly for nitrates, are harmful to the human body and elevated concentrations can lead to methemoglobinemia, a blood disorder. Slaughterhouses must operate more efficiently to stop their pollution and invest capital to purchase newer technologies that help protect water quality.”

TEXAS: Brian Zabcik, Clean Water Advocate of Environment Texas, said: “Texans love barbecue – but nobody ordered a side of water pollution along with our meat. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality needs to issue stronger water pollution control permits for the slaughterhouses in East Texas and elsewhere – and then enforce them, so they stop contaminating our waterways.”

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS:

The report concludes that the state and federal governments should do more to reduce water pollution from the slaughterhouse industry by:

1) Stepping up both state and federal enforcement of permit violations by meat processing plants;

2) Strengthening outdated EPA standards for water pollution from meat processing plants nationally (which have not been updated since 2004) with tighter limits for nitrogen, bacteria, and other pollutants, along with better monitoring;

3) Tightening up state pollution control permits to reduce discharges of wastewater to rivers, lakes, and streams that are so polluted that they are impaired for public use;

4) Prohibiting irresponsible disposal methods, such as spraying waste onto farm fields that are close to homes, whose drinking water wells can be contaminated.

For audio of the October 11, 2018, telephone press conference, click here.

The Environmental Integrity Project is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization, based in Washington D.C., that protects public health and the environment by investigating polluters, holding them accountable under the law, and strengthening public policy.

Media contact: Tom Pelton, Environmental Integrity Project (202) 888-2703 or tpelton@environm915stg.wpenginepowered.com

###