New Report: EPA’s Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification Plans Fail to Ensure Safe and Long-Term Carbon Storage

Washington, D.C. – The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s rules for monitoring and verifying that sequestered carbon dioxide stays underground fail to ensure safe and long-term carbon storage, according to a new report by the Environmental Integrity Project.

Federal regulations require companies seeking billions of dollars in federal subsidies to capture and bury carbon dioxide – a key part of the Biden Administration’s climate policy – to have monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) plans approved by EPA under its Greenhouse Gas Reporting program.

EIP’s report, “Flaws in EPA’s Monitoring and Verification of Carbon Capture Projects,” analyzes the 21 MRV plans approved so far and reveals that the plans are insufficient to prevent leakage of carbon dioxide and difficult to enforce. Among the report’s conclusions:

- EPA does not require specific monitoring strategies or technologies, allowing companies to write their own rules.

- The plans contain ambiguous language that lack explicit monitoring timelines or quantification strategies, with some saying companies will only continue with monitoring actions “if beneficial,” or allow companies to “determine the most appropriate method” to quantify leaks.

- The plans are difficult to enforce, with no third-party verification of data self-reported by companies.

The effectiveness of these monitoring and verification plans are important because increased subsidies for carbon capture projects approved by Congress last year, which could cost taxpayers $30 billion over the next decade, inspired a wave of industry announcements about new carbon capture projects and hubs. EPA is currently reviewing 58 applications for 169 carbon disposal wells of one variety, called “Class VI” wells, which are designed for the long-term sequestration of climate-warming waste generated by petrochemical plants and other industries.

“Before this flood of carbon capture and sequestration projects becomes operational, EPA needs to enact strong industry regulations that can protect the environment while combating climate change,” said Eric Schaeffer, Executive Director of the Environmental Integrity Project. “EPA must ensure the monitoring plans contain comprehensive and clearly defined monitoring strategies that can adequately detect leaks, prevent environmental harm, and confirm that carbon is successfully stored long-term.”

Congress first created a tax credit for carbon sequestration in 2008. Lawmakers then expanded it in 2018 and again with the Inflation Reduction Act, which was signed by President Biden on August 16, 2022.

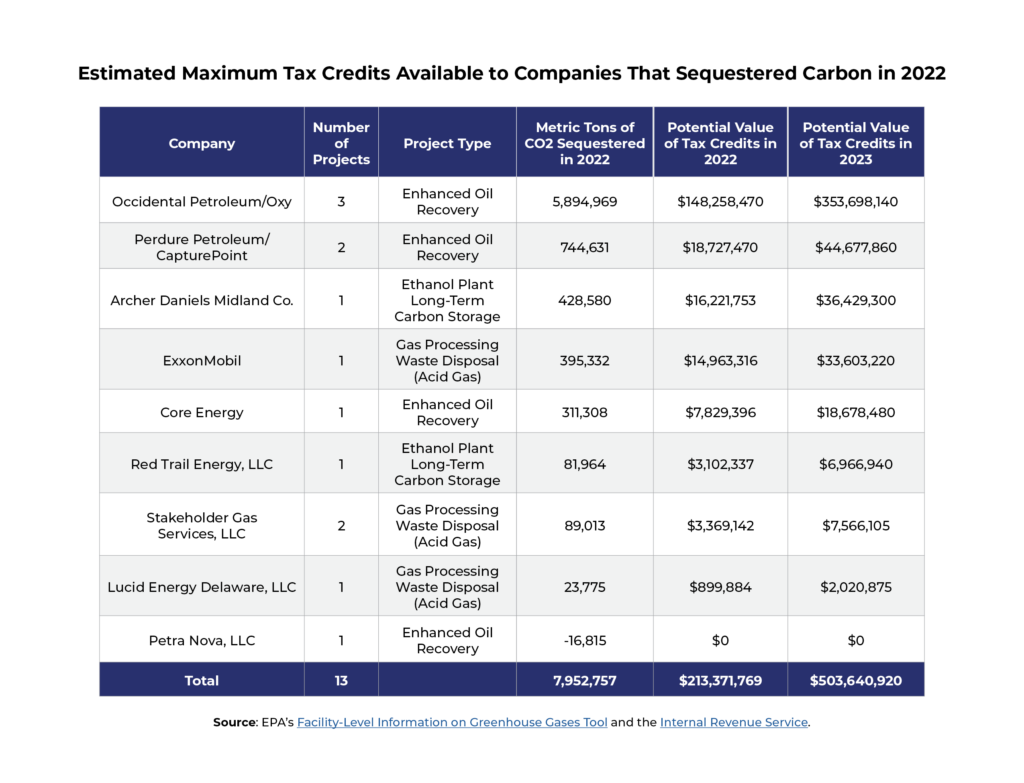

The oil, gas and ethanol industries reported capturing and sequestering nearly 8 million metric tons – about the same as what would be emitted by two coal-fired power plants – of carbon dioxide in 2022, an amount worth an estimated $213 million in federal tax credits that year, according to EPA data. Sequestering the same amount in 2023 could be worth up to $504 million, thanks to a sharp increase in the value of tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Sixteen of the 21 monitoring and verification plans approved by EPA as of October 31, 2023, were submitted by oil and gas companies, which stand to benefit the most from the push for carbon sequestration. Ten of the sites are using carbon dioxide for enhanced oil recovery, a method of freeing up hard-to-reach oil by injecting carbon dioxide into the oil field. Six are disposing of waste from gas processing plants by injecting carbon dioxide-laden acid gas into the ground.

“Enhanced oil recovery and acid gas projects should not be eligible for tax credits,” said Preet Bains, author of the report and research analyst for the Environmental Integrity Project. “Carbon injected at these sites is secondary to the production of more fossil fuels. This undermines the primary goal of carbon sequestration and puts taxpayer money into misguided efforts to confront climate change.”

The need for comprehensive, accurate monitoring of buried carbon is compounded by the huge number of old wells at some of the disposal sites, especially oil fields which have been active for decades. These wells present a huge challenge to permanent storage of carbon because they are holes through which CO2 can leak.

For example, the Wasson San Andres Field in the West Texas Permian Basin, where oil production has been ongoing for at least 50 years, has nearly 4,700 known wells perforating the area. Buried carbon could leak out through these thousands of openings.

For a spreadsheet with details on all 21 plans, click here.

The Environmental Integrity Project is a nonprofit organization, based in Washington, D.C., and Austin, Texas, that is dedicated to enforcing environmental laws and strengthening policy to protect public health and the environment.

Media contact: Tom Pelton, Environmental Integrity Project (443) 510-2574 or tpelton@environmentalintegrity.org

Image: Wikimedia Commons